According to Diabetes Canada, one third (33%) of Canadians will likely have either diabetes or one of its forerunners by 2032. The downstream healthcare burden and costs, on top of the stretched Canadian healthcare system, are staggering. Diabetes, and its related metabolic disorders, contribute to 30% of strokes, are the leading cause of blindness, cause 40% of heart attacks, 50% of kidney failure requiring dialysis, and 70% of leg and foot amputations. It’s an escalating global problem according to both the WHO (World Health Organization) and the IDF (International Diabetes Federation).

This post will highlight causes for this rising health crisis and offer solutions which all citizens need to take responsibility for. The focus will be on Type 2 Diabetes (Type 1 diabetes usually starts in early life and has a very different cause than the more common Type 2 variety), and its frequent forerunner, metabolic syndrome.

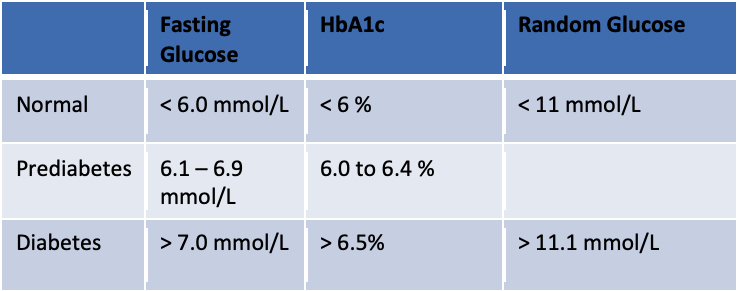

How we diagnose diabetes and prediabetes

Table 1 below shows the simple blood tests used to diagnose diabetes. Glucose is one of the two molecules in sucrose (common sugar), the other being fructose. A fasting glucose is a blood test that measures the blood sugar circulating in the bloodstream after a typical overnight fast. A random glucose is taken regardless of fasting state. The HbA1c refers to glycosylated hemoglobin. This is the per cent of hemoglobin (in red blood cells and which carries oxygen) that has a glucose molecule attached to it. The longer the hemoglobin is exposed to elevated blood glucose levels, the larger the per cent of hemoglobin that becomes glycosylated (or “sweetened”) by a glucose molecule. This is a good measure of average blood sugars over the recent three months.

There is another blood test which can detect earlier signs of prediabetes before the fasting glucose begins to rise. Insulin levels can be measured to detect hyperinsulinemia, but this is not a standard test and rarely used by most doctors or nurse practitioners. Insulin becomes elevated because there is resistance to it by muscle cells and fat cells, requiring ever increasing amounts to keep the blood sugar normal. This insulin resistance is a major factor leading to full blown diabetes and all its end organ damaging effects. And it is almost always present in what we now call metabolic syndrome.

What is metabolic syndrome?

Metabolism is the way our body converts the energy in our food, into the energy needed by our cells (such as brain cells and muscle cells), to do their job (cognition or movement). The term metabolic dysfunction simply refers to something awry in the pathway between food energy to cell energy (mostly ATP or adenosine triphosphate). Diabetes, prediabetes, and hyperinsulinemia are all evidence of metabolic dysfunction.

Metabolic syndrome is now known as a specific condition that can be diagnosed by the presence of 3 (or more) out of the following 5 conditions:

- High blood pressure (essential hypertension)

- High triglycerides (on a fasting blood test)

- Low HDL cholesterol (also on a fasting blood test)

- Large waistline (waist > 40” (94 cm) in men, 35” (82 cm) in women)

- Elevated fasting glucose (> 6.0 mmol/L)

While not required for a diagnosis, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is also often associated with metabolic syndrome in women. About 40% of adult woment and nearly 1/3 of adolescents with PCOS have metabolic sydrome.

It is estimated that in North America, 1 in 3 adults have metabolic syndrome. Some estimates are even higher, given the rising rates of obesity here.

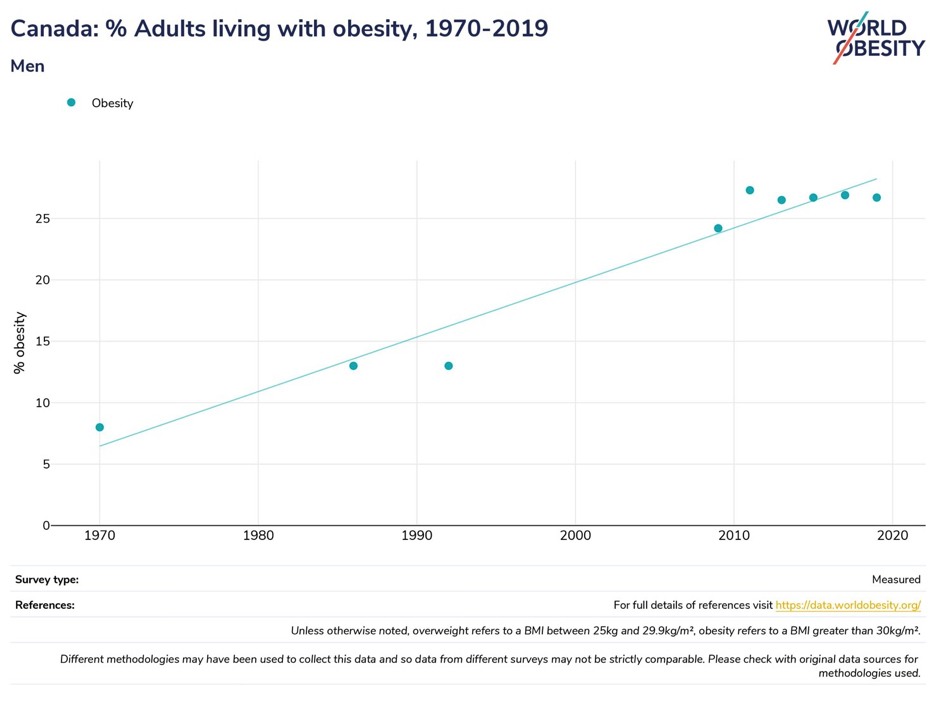

Obesity rates in Canada

The Figure 1 chart below documents the rising rates of obesity in Canada between 1970 and 2019. The definition for obesity here is a BMI (body mass index) of 30 kg/m2 or more.

This shows prevalence rates of obesity over 25%. But even more significant, is that when overweight Canadians are added (BMIs between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2), the rates jump to over 60%.

Being overweight or obese is a major risk factor for insulin resistance and its downstream effects on both physical and mental health.

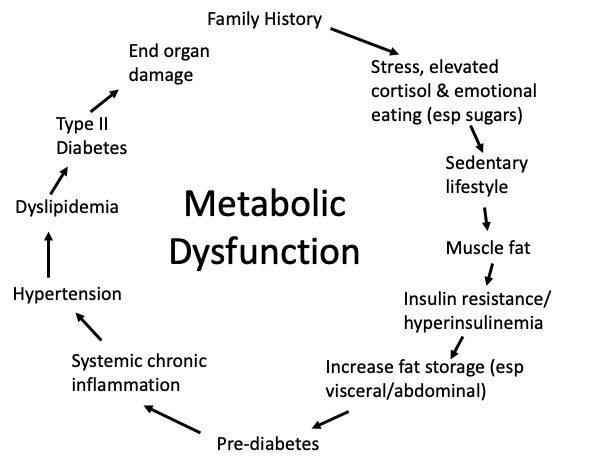

The metabolic dysfunction pathway

Figure 2 is a typical pathway that leads to ill-health on multiple fronts. It’s also a cycle because there is a tendency to perpetuate itself after end organ damage begins; stress invariably increases, as does emotional eating and a sedentary lifestyle.

Type 2 diabetics often have a family history for diabetes. There are also ethnic differences, with some increased risk among First Nations adults, as well as South Asians, for example. With recent understanding of epigenetics, it is unclear how much of inherited diabetes is genetic (nature), versus epigenetic (nurture). Which leads to step 2 of our cycle—stress.

Prenatal and childhood stressors (known as ACEs, for adverse childhood experiences) predispose a child (and the later adult) to hyper-vigilance, and elevated levels of the stress hormone cortisol. This is part of the “fight or flight” hormonal system designed for our protection from danger. One of the functions of cortisol as a stress hormone is to ensure adequate blood sugar levels for fighting or escaping. And, with prolonged stress, and prolonged elevated cortisol levels, appetite is likely to increase, with sugar craving. This may start a long road beginning with childhood obesity.

Emotional overeating often co-exists with a sedentary lifestyle. It is now thought that the first step toward insulin resistance is fat deposition into muscles (like marbled steak). Clearly, excess carbohydrates and inactive, flabby muscles, play a role.

With elevated insulin levels that to this point can keep blood sugars (and tests) in normal ranges, something sinister happens in the abdominal cavity in particular. One of the functions of insulin is to push excess calorie energy into storage, either in the liver as glycogen, but also into fat cells. The fat cells in the abdomen, including organs like the liver and the pancreas, and in the omentum (a fatty apron-like layer over the intestines) begin to swell with fat. This often leads to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and fatty pancreas. This is where the abdominal girth measurement noted above as a finding in metabolic syndrome is relevant. You may have read of the “apple” shaped body habitus versus the “pear” shape. It is the apple that may be a problem. There are other fancy tests that some private clinics recommend measuring abdominal (also known as visceral) fat. Here in our health system, an abdominal ultrasound will often reveal a fatty liver. And a fatty pancreas, where insulin is produced, may begin to slow insulin production.

By this point on our cycle, it is likely possible to find evidence for prediabetes on careful testing (either a glucose tolerance test or a fasting insulin level). But what is most disturbing at this point toward a healthy lifespan (so-called “healthspan”) is systemic chronic inflammation. And this has a lot to do with two factors: 1) chronically elevated cortisol levels and 2) abdominal fat cells that leak proinflammatory cytokines (these are substances that cause low-grade or frank inflammation).

Both chronically elevated cortisol levels and systemic chronic inflammation affect brain and nervous tissue health. This is called neuroinflammation, and now understood to be a significant contributor to mental illness (such as depression and bipolar illness and the neurodegenerative disorders (such as dementia). This is also likely a significant factor in lingering symptoms after a (sometimes minor, or repeat) concussion.

Chronic stress, elevated cortisol, and chronic inflammation all contribute to many of the chronic diseases taking up so much of our healthcare resources: cancer, strokes, heart disease, chronic pain, autoimmune disorders, etc.

Once the cycle reaches the top again, lifestyle patterns, stress, and genetic material, all get passed to the next generation, and the transgenerational cycle begins again.

How do we interrupt the cycle?

Clearly, the earlier we can intervene in the cycle, the better outcomes we can expect both individually, in families, and in the community. Family and relational health that can welcome a newborn into a stable, loving environment is key. Then physical activity and a healthy diet of whole foods away from excess sugars and carbs, in particular ultra-processed foods, are essential for all. And meaning and purpose, contribution, and community, rather than the “me” of individualism. Healthcare professionals need to be trauma-aware and able to address psychosocial factors early, long before downstream disease takes hold.

I support the Live Well PEI initiative. Let’s get the message out.

I also believe we need to convene roundtable discussions with key stakeholders from disciplines including healthcare, education, the faith community, charities, politics, sports and fitness leaders, business leaders, and parents to explore the cultural transformation changes needed to ensure resilient and thriving families and workforce.

This is no easy task. But I for one, believe that none of us is as smart as all of us. There are, for example, lessons to be learned from educational and parenting styles from other countries (look at Finland’s educational success, for example).

I am encouraged by the collaborative practice model being rolled out (Patient Medical Homes) on PEI. But to be successful, we as citizens we must ALL do our part as we are all OWNERS of our publically funded healthcare system—for the sake of our elders and future generations.

If you would like to be part of roundtable discussions, please contact me, or the Live Well Health Promotion Team at livewellpei@ihis.org

My team and I also offer a 10 hour Well-Being Masterclass that can be offered in a weekend retreat setting or over 5 evenings. We cover all four quadrants of a healthy and thriving lifestyle: Physical disciplines, Mental health and character, Spiritual meaning and purpose, and Relational belonging nad connectedness. Contact me for more information or to request the course.

Hendrik Visser, MD, CIME

Further reading

The Deepest Well: Healing the long-term effects of childhood adversity by Dr. Nadine Burke Harris (deep dive into the lifelong effects of childhood adversity and trauma, and solutions)

Community: the structure of belonging by Peter Block (how to begin roundtable discussions that use the power of collective wisdom and passion)

Hidden Potential: The science of achieving great things by Adam Grant (great info on parenting and education)

The Coddling of the American Mind: How good intentions and bad ideas are setting up a generation for failure by Jonathan Haidt & Greg Lukianoff (wisdom on parenting and education)

Metabolical: The lure and lies of processed food, nutrition, and modern medicine by Robert H. Lustig (deep dive into the medical science behind metabolic dysfunction and our modern diet)

Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span by David Furman et. al. (Nature, 05/12/2019)