When I began my medical career in an underserved part of West Africa in 1980, we trained village health workers using this book:

Where There Is No Doctor is a great book title. It was and continues to be a resource for underserved areas in the Global South.

Then I saw this headline in the Globe and Mail:

The author, Dr. Sanfilippo, a professor of medicine at Queen’s University, paints a bleak picture with around 6 million Canadians (15% of the population) without a family physician.

That made me think, “How did a G7 nation come to share the health challenges of low and middle-income countries?”

In this post I want to add some reflections on the reasons why so many Canadians do not have a family doctor. More specifically, why are young medical graduates not choosing a residency in Family Medicine and choosing other career paths.

Some history

From the dawn of Medicare in the early 1960s, to the early 1990s, was what I refer to as the “golden era” of family medicine. Prior to 1960, family doctors had significant accounts receivable from patients and families unable to pay their medical bills, and often worked pro bono. Suddenly, under Medicare, they were getting paid for their work, albeit at rates per service below other professionals such as dentists or lawyers, or colleagues south of the Canadian border. Their large practises and high throughput gave them a decent and satisfying living.

In the early 1990s, both the federal and provincial governments began to recognise that the healthcare cost trajectory under Medicare would likely be unsustainable. There was talk of too many doctors and nurses. Medical school enrollments were reduced. Recently graduating nurses couldn’t find work in Canada and were recruited to the United States (I have family members who moved to the US as nurses, married and settled permanently there).

But in my opinion, a very significant reason that family medicine lost its appeal is that the official Canadian solution to rising healthcare costs was to ration access and create gatekeepers.

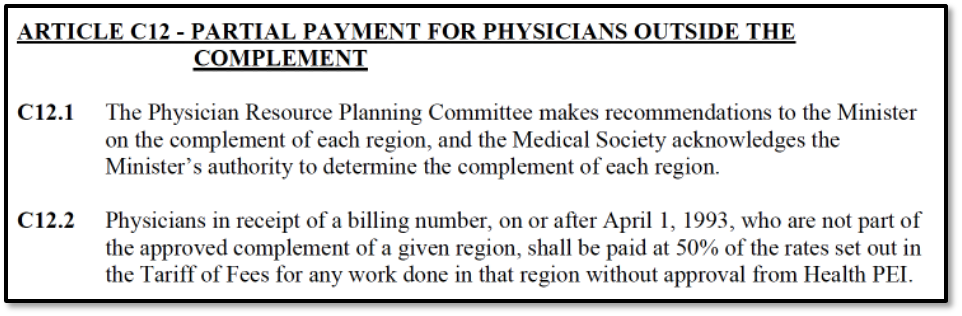

Unfortunately, those gatekeepers were mostly family physicians. Here on PEI this began the much hated and maligned “complement system.”

Here family physicians especially lost agency and intrinsic motivation, both well documented in the literature to be essential in self-determination theory and well-being. This, along with relatively poor pay under the fee-for-service system further alienated young graduates. Under fee-for-service, the emphasis became volume (10 minute consultations or less), rather than quality. Young doctors wanted a better “work/life balance,” as it became known. The larger practises of retiring physicians were unmanageable for younger successors leaving patients without the access they were used to. Doctors began to burn out under this load, only to become exacerbated during the Covid-19 pandemic. Cultural changes in patient expectations and demands also contributed to making family medicine hard.

Many Canadian provinces began to move family doctors to a salaried model, like the civil service. Here throughput became a problem, and some jurisdictions, including PEI incentivised extra work. However, decreased patient access and reduced practise sizes (panel size), began the unaffiliated (also known as orphan) patient problem noted in the Globe and Mail piece (15% of Canadians or 6 million). This was exacerbated by a growing population of immigrants and the increased needs of the elderly.

Some jurisdictions began to experiment with multidisciplinary health centres which the College of Family Physicians calls “Medical Homes.” These included nurse practitioners as well as other allied health professions working in collaboration under one roof. Initial success was reported in Ontario, but their roll-out there was halted as they were deemed too costly.

Here on PEI this is now the model going forward. I have always applauded and supported this model. I worked with non-physician primary healthcare workers and midwives in Africa and we were able to serve a population of 2 million in a hospital roughly the size of the Queen Elizabeth Hospital with around 8 physicians (albeit with much more limited resources and infrastructure). But lessons can be learned here as a rich country since we now also have limited (human) resources.

To date, the PEI registry of unaffiliated patients has not been positively impacted (36,000 or 20% of Islanders).

What are the solutions?

First, two motherhood type aphorisms:

- “We cannot keep doing what we have always done and expect different results.” (Some say this is the definition of insanity).

- “The whole world is short-staffed.” Depending on other nations for recruitment will ultimately be futile as everyone is vying for the same nurses and doctors. And in my opinion, for a rich country to poach healthcare staff from poorer countries is less than moral or ethical.

Unity in community

We must begin with the recognition that we are ALL owners of our publicly funded healthcare system. There are longstanding “US versus THEM” dysfunctions in our system very vividly highlighted in recent media reports and townhall meetings. And a prior resignation of the entire Health PEI Board.

A “Truth and Reconciliation” moment similar to those with the injustice that our first nations endured should be undertaken in regard to the decision in Canada to ration healthcare over the backs of primary care gatekeepers. In my opinion, this is akin to abuse. This may sound strong but I practised on PEI in the 1990s and we were never officially mandated to be gatekeepers–it was subtle and under the radar.

Then, I believe we need to draw together in roundtable multidisciplinary forums to brainstorm out of the box solutions. No idea or solution should be immediately discarded as far-out. A great example for this is work by Peter Block in Community: The structure of belonging. No podium or platform or high-powered consultant to tell us how to do it. Smart people from differing disciplines sitting down in circles to build on our strengths rather than focussing on problems.

Train for real needs – and don’t burn them out before they launch

Much training is currently either wasteful or not helpful for the real needs. A four-year undergraduate degree for Medical School is unnecessary (in the UK Medical School starts after high school). I have been promoting a “gap year” doing something hard (for example, either in the Canadian north or internationally) which in my opinion (and that of other experts) would create far more people skills (EQ) and resilience than an undergraduate liberal arts or science degree.

Similarly, training RNs to be bedside nurses first and then partly through their career to train them as NPs is not in my opinion efficient. This is also problematic because we are depending on a short pool of good bedside (ER and ICU) nurses to bring them into primary care. The expertise for these disciplines is vastly different. I have written about an alternative credentialling stream (see my white paper) that could begin to produce excellently trained primary care workers for medical homes in TWO YEARS from now.

Many employers from differing industries have told me that our primary and secondary education system is not effectively training our young people for the real world of work. Parents and educators must be part of long-term discussions and solutions to prepare young people for tomorrow’s healthcare careers.

Transformational leadership

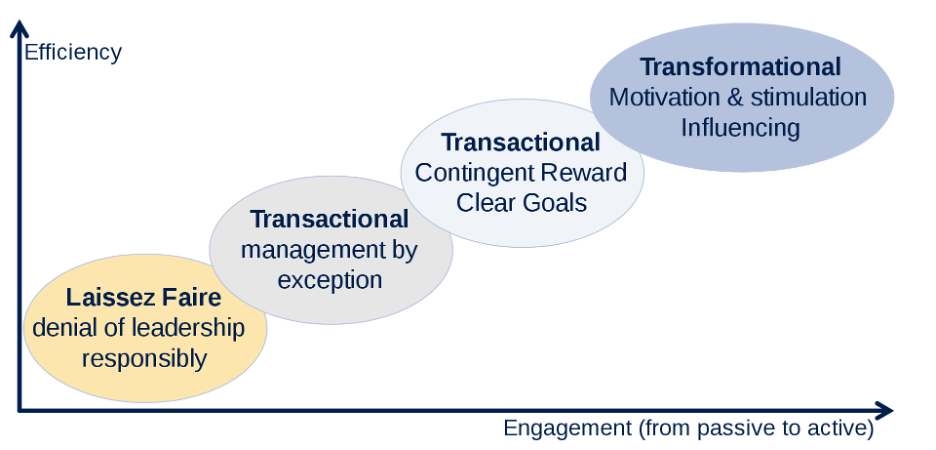

The recent crisis in the Prince County Hospital was precipitated by what leadership experts call “transactional leadership.” This is an older hierarchal leadership style hearkening back to the industrial revolution. It is a “Do as I say,” model.

Leadership experts in most every industry now agree that a Transformation Leadership style is needed in today’s world of work, especially with younger workers. I have written about the difference here.

I have worked as an occupational medicine physician for the last five years of my career and have seen the difference great bosses make in their workers throughput and resilience. This is well documented in the occupational literature (particularly Gallup data).

A famous quote by Simon Sinek is in order here:

“Leadership is not about being in charge. Leadership is taking care of those in your charge.”

Simon Sinek

Measure to find the “pinch points”

The late legendary leadership and management expert Peter Drucker said, “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.”

Some things to measure (to better manage):

- Wait times for an urgent appointment

- How long does it take to get a receptionist on the phone?

- How many ER visits are unnecessary if access for primary care was ideal?

- How many patients an hour are clinicians seeing? Expected to see?

- How effectively are incoming calls for appointments triaged for urgency?

A group of retired physicians, including family physicians, have authored a proposed workflow template that we believe would help Medical Homes become efficient with excellent outcomes and patient satisfaction. Click here to download and read it.

Upstream prevention

The entire theme of this website is finding “upstream solutions,” with more effective prevention strategies for many chronic diseases we now know have a singular root—systemic chronic inflammation.

Yes, we will need rescue gear and lifeboats, but a safety net above the falls would keep us all less busy rescuing people. Here is another advocacy group with similar thinking.

Psychosocial stressors and life trauma are now known to signficantly affect both childhood and adult health. Research has shown that at least 50% or more of presentations of patients for primary care are for issues related to these factors. Loneliness has also been identifiied as a large factor. There is a place for charitable, community, and faith based institutions to fill some of these needs, alleviating pressure on the biomedical healthcare community. (see work done by James Maskell at HealCommunity).

In summary

“None of us are smarter than all of us.”

Ken Blanchard

Let’s begin by creating circles of connection. Indiginous populations everywhere have always problem solved in circles. We can too. The stage and the podium were Greek inventions.

We need to train for real needs, beginning with parenthood and kindergarten, then schools, colleges, and universities. Put daily Phys Ed into every level from kindergarten to Grade 12.

Become a transformational leader and love your people like family.

Measure and identify “pinch points” in order to widen them and “relieve the pressure.”

Teach lifestyle choices to deal with the new enemy known as sugar, and its effects on insulin resistance and systemic chronic inflammation.

And finally, we need to be prepared to learn from other jurisdictions and countries rather than always needing to “re-invent the wheel.” I wrote about that in the previous post on the Times Report from the UK.

I completely agree with Dr. Sanfilippo in his Globe and Mail article:

The family physician shortage has multiple causes beyond the training process. Expectations, practice settings and compensation models are all contributing to the issue and require similarly thoughtful and disruptive innovation. We should not be passing the problem along to elected municipal officials. The time has arrived for a high-level approach involving all participants in the training continuum, focused on the current and future needs of the Canadian public. They deserve much better.

Dr. Anthony Sanfilippo, Queen University

I welcome feedback and dialogue to flesh out these ideas. These views are my opinions based on my own experiences practising here on PEI as a family physician for 32 years, as an occupational medicine physician with the Workers Compensation Board for 5 years, and in my early career for 5 years in West Africa, and subsequently leading small capacity building medical teams to East Africa as well.

Thanks for your interest,

This post is available as a PDF document upon request. Contact Dr. Visser at: https://drhendrikvisser.com/contact/

See also: