There is much handwringing and finger pointing regarding the state of Primary Healthcare in Canada. If not daily, certainly weekly, media reports highlight the shortage of family physicians. And deaths from virtual care misdiagnoses. Groups such as our own Retired Physicians Advocacy Group are writing and posting reports with suggested solutions.

Here is a recent one, Primary Care Needs Our Care, available on the OurCare.ca website, principally authored by Dr. Tara Kiran, a family physician from St. Michael’s in Toronto. This included a national survey and several provincial “Priorities Panels,” essentially multidisciplinary round tables. Their key themes and recommendations are identified on page 7.

I would recommend a close reading of this excellent work by our political and healthcare leaders.

The angle of more spending on prevention and the determinants of health was emphasized by another group called Generation Squeeze. Their report, Health is More Than Medical Care, is authored by Paul Kershaw, Ph.D, UBC School of Population and Public Health. Their website is GetWellCanada.Ca . The CBC recently highlighted this work, reporting that the authors “call for better funding of housing, child care and education to improve population health.”

In this post I will add some additional reflections on how I believe we got where we are. The corollary is of course that by identifying these factors, we could potentially reverse these barriers in the long term.

I will highlight what I believe to be four contributing factors:

- Primary care in Canada has entered a “grey zone” – a liminal state

- “Everything rises and falls on leadership” – and on followership

- The workforce (and society) have become “fragile” – not only a lack of resilience

- Mainstream western medicine continues entrenched on the Cartesian foundation of dualism

Primary care has entered a grey zone

The space between the end of an era and the faltering or sputtering new era is sometimes referred to as a “grey zone.” Or a liminal state. The leader’s vision for the new era may be foggy and there may not be unity or buy in by all followers. Policies and procedures are likely being tested as drafts. So, the new era may lead to polarization, conflict, and poor performance.

The “golden era” of family medicine began in Canada under Medicare in the early 60’s and had a quite abrupt end in the 1990s when Canadian political leaders decided to address rising healthcare costs by rationing access. For those with a memory of those days, Dr. Marcus Welby was the ‘poster boy’ of this era. Everyone had their own caring, kind, family doctor. They were generally self-led, owner operators of their own small (or larger clinics) domain. They got paid for their work, although often poorly compared to other similar professionals. They hired their own staff. Through volume and large practises, they (I included) made a decent living.

The new era of family medicine is marked by the “Medical Home” concept, interdisciplinary teams under one roof. Globally, this is not a new idea. Personally, I entered the profession in West Africa in 1980 under this model, and together with non-physician primary health care workers, nurses, and midwives, we (around 8 to 10 MDs) largely looked after a population of around 2 million people.

But here in Canada, and on PEI, we have not yet “hit our stride,” under this new model. Where promises were made that this new way would quickly eliminate the “patient registry” of individuals and families without a family doctor or nurse practitioner, this has not yet happened. Negotiations here (and in other provinces) are underway to appropriately remunerate family physicians under the new model. We are all hopeful that this will attract more young physician graduates into a family medicine career.

But meanwhile, here is what is missing, in my opinion—synergistic teamwork. Medical homes can only be high performing when the sum of the individual contributions is greater than those individuals working on their own (or in other facilities). That’s the definition of synergy: 1 + 1 > 2.

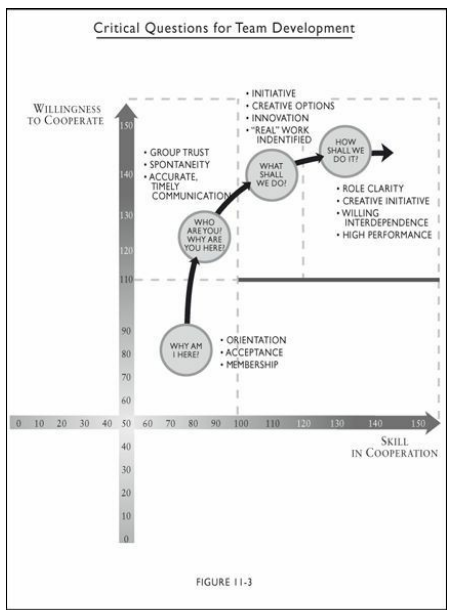

In his book, The Performance Factor, author Pat MacMillan has illustrated what is required for a team to be high performing and which questions must be addressed (Both Skill in Cooperation and Willingness to Cooperate are needed – see figure below):

He writes,

“Largely through ignorance, many teams never address these questions and spend most of their time drifting through a fog of ineffectiveness characterized by defensiveness, mistrust, game-playing, and politics, apathy, competition, and conflict.”

Pat MacMillan, Location 3640

The willing interdependence needed is quite countercultural to our current societal trend toward hyper-individualism. I am however, hopeful that our PEI Medical homes are becoming high performing teams and much rests on how they are being led—their team leader.

Leadership and followership

According to leadership expert and prolific writer, John C. Maxwell, “Everything rises and falls on leadership.” Family physicians were traditionally self-led and intrinsically motivated. And in the historical hierarchal command and control healthcare industry, physicians were over nurses, and so on down the line. In this new era, the leadership dynamics are changing, and many managers are nurses or business graduates.

Many family physicians are now opting to be led. So, they need to be followers. To quote MacMillan again, they need to be “rowing in the same direction.” This means a shared passion for the mission and vision of the organization. A social contract marked by civic responsibility for the greater community good, rather than one’s own self-centered needs (a healthy interdependence) is what I believe is needed.

Robert Bly was already warning readers of the trend toward individualism back in 1996 in The Sibling Society:

“We all recognize that our emphasis on individualism in the West has dimmed whatever instincts Western youth might have had to preserve the troop. For some time now our own spark of life has been more compelling, more important to us, than the flame of the larger group.”

Robert Bly, The Sibling Society

Many employees in the healthcare industry (and the workforce in general), including physicians, have also been influenced by the so-called “slow productivity movement,” highlighted by media reports of “quiet quitting” and “the great resignation.” The Covid-19 pandemic certainly encouraged these trends. Certainly, this trend is not all bad. Workism (work as god), and workaholism (an addiction), both damage individuals and families. Cal Newport has written a fascinating book on this, Slow Productivity: The Lost Art of Accomplishment Without Burnout. He highlights 3 ways: 1) Do fewer things 2) Work at a natural pace and 3) Obsess over quality.

High performing Medical Homes without chaos and unnecessary hurry or working late are possible. It requires great role clarity, efficient phone service (or on-line equivalent), great triaging, and a system of saving space for same day (in-person) urgent cases. And the efficient use of IT. Our Retired Physicians Advocacy Group has written a draft potential workflow template.

But there will be times when we will need to do hard things (like during a pandemic, or a natural disaster). How we learn to handle the winds of adversity are a key to high performing teams and personal well-being and resilience (by becoming antifragile).

Cultural fragility

A lot has been spoken and written recently about resilience, the ability to bounce back to baseline after something hard. Family medicine is hard. I know. I was there for 32 years looking after over 2000 people. It takes commitment and dare I say, “love” for your patients and your community.

In his scholarly book, Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder, Nassim Taleb asserts that resilience is not enough but that we need to grow from doing hard things and become what he calls “antifragile.” It’s the idea of “posttraumatic growth.” In living organisms, it is called hormesis (small incremental stressors make an organism stronger).

He writes,

“Much of our modern, structured, world has been harming us with top-down policies and contraptions (dubbed “Soviet-Harvard delusions” in the book) which do precisely this: an insult to the antifragility of systems. This is the tragedy of modernity: as with neurotically overprotective parents, those trying to help are often hurting us the most. If about everything top-down fragilizes and blocks antifragility and growth, everything bottom-up thrives under the right amount of stress and disorder.”

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Antifragile

Other authors and researchers have similarly been documenting societal trends toward fragility:

- Michael Easter in The Comfort Crisis

- Jonathan Haidt in The Coddling of the American Mind and just released The Anxious Generation

- Abigal Shrier in Bad Therapy: Why the Kids Aren’t Growing Up

- Jean Twenge in Generations

Today’s hyper-individualism will not easily morph into a healthy interdependence and the higher civic good. Unfortunately, polarization and tribalism based on religion, gender, or skin colour, has worsened our corporate stress levels and fragility. When we hear the line, “our community,” it often refers to a subset rather than our actual geographic village or town.

Teaching children to become healthy interdependent, selfless adults, must start in the family and parenting. Then schools and educators, faith communities, and invested non-profits must fashion curricula and training to counter today’s “sibling society.”

I have written before about the need for roundtables to explore these ideas and offer real-life advice to leaders and parents to ensure a more robust and antifragile healthcare workforce in future generations. Jonathan Haidt in The Anxious Generation offers very practical advice on ways our children might be raised in the presence of social medial, smartphones, and AI.

Cartesian dualism

René Descartes (1596–1650) taught that the mind and body were separate. While he was ahead of his time in the 1600s, he wasn’t entirely correct. In his book, Descartes’ Error, neuroscientist Antonio Damasio showed that Descartes missed both the role of emotions, and the unity of mind and body. To highlight the error, Damasio writes,

“This [correction] is anchored in the following statements: (1) The human brain and the rest of the body constitute an indissociable organism, integrated by means of mutually interactive biochemical and neural regulatory circuits (including endocrine, immune, and autonomic neural components); (2) The organism interacts with the environment as an ensemble: the interaction is neither of the body alone nor of the brain alone; (3) The physiological operations that we call mind are derived from the structural and functional ensemble rather than from the brain alone: mental phenomena can be fully understood only in the context of an organism’s interacting in an environment.”

Antonio Damasio, Descartes’ Error

Unfortunately, much of Western medicine continues in a biomedical model that we built on Descartes’ debunked dualistic theory. This results in a fix-it after its broke approach rather than upstream preventative strategies that include psychosocial (emotional) risk factors, which we now know play a huge role in adult health and chronic disease. The famous ACE (Adverse Childhood Experiences) study has definitively shown this.

A 2015 paper, Somatoform Disorders and Medically Unexplained Symptoms in Primary Care, showed that over half of presentations to primary care have psychosocial stressors as the root etiology. My fellow retired family physician colleague, Dr. Peter MacKean, has written how family doctors require more training in psychosocial diagnosing and interventions then currently offered in medical school and family medicine residency.

Many other physician writers write of this lack in physician training:

- Dr. Gabor Maté in The Myth of Normal

- Dr. Nadine Burke Harris in The Deepest Well

- Dr. Peter Attia in Outlive

In my own work in Occupational Medicine at the Workers Compensation Board, I saw firsthand how psychosocial factors play a huge role in the outcome of workplace injuries. In some cases, it proved to be the difference between permanent impairment and worklessness versus excellent recovery and successful return to gainful employment.

As frontline clinicians in primary care, both family physicians and nurse practitioners (and other allied health workers), gain a deeper appreciation for a trauma-informed bio-psycho-social approach to prevention, investigation, and management of disease, good research predicts that outcomes and population health will improve.

Conclusion

Everyone is agreed that an efficient primary care system is the bedrock for a great healthcare system and can help mitigate heavy reliance on specialists, intensive and expensive treatments, and poor access to urgent care.

Strategies for long-term solutions will be difficult to agree on by key leaders in politics, healthcare, and educators (including healthcare worker education). The place to begin is with active listening and unselfish dialogue.